Out of Reach: Space for a Secret Speaker

October 20, 2013 Blog Leave a comment

If you look hard enough, we tell our children, you can see a man’s face peering at you from the surface of the Moon. It’s a place where the temperature can range from extremes of 123 to -153 degrees Celsius. Yet a face of craters, slightly lopsided and uncanny, makes a lump of rock so inhospitably alien become something familiar, even human.

One of the first Christmas presents I have strong memories of using is a telescope. An inexpensive model; the kind you’d be happy to let a child swing round when it doubles up as as a collapsable sword. But, despite its small cost, it was able to bring something very large to the front of my childhood mind.

Created by craters: the result of impacts and whatever other problems you might encounter when you’re a celestial body that’s been floating around in space since forever. There is the face on the Moon.

Yet it is a mirage. One which is created by our instinct to see faces on everything, Pareidolia.

Obviously I didn’t know the name for the phenomenon when I was a kid. But I do remember Dad, sat out in the garden with me at night time, explaining the face was a trick. Really, it didn’t matter. I still had the Moon at the front of my mind. Or at least, in front of it. Because a telescope holds the Moon just centimeters away from you. If your arms were only a little bit longer you might be able to touch it. But without the telescope, the distance seems impossible. The fact that people have been there (“Really?” “Yes.”) incredible.

So, how did it happen?

In the 1940s scientists around the globe frantically populated laboratories and began serious work toward a goal that has, no doubt, occupied the minds of men and women since shortly after the ability to think happened. Way before I owned a telescope. Space: how do we get there?

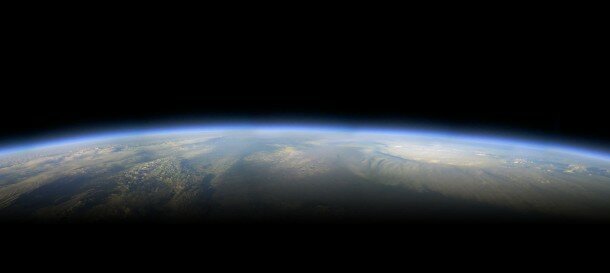

Now, and I’m sure you know this already, Space, if you’ll forgive a general definition, is really big. No hyperbole on Earth is adequate to describe how unbelievably, gigantically massive our subject is, as it literally goes on forever. Simply writing a post about it tempts you to let loose a dizzying display of adjectives and astonishing astronomical facts. Indulge me.

So, the observable universe is a sphere with a radius of roughly 46 billion light years. Wikipedia tells us that a light year is an “astronomical unit of length” where astronomical is not hyperbolic but scientific. It goes on to say that one light year is ”equal to just under 10 trillion kilometers.” Damn, son.

That means, if the average person is roughly 1.6 meters tall, and if I have worked this out correctly, it would take 2,875,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 or roughly 2.9 nonillion people, all of whom perfectly balanced on the head of the last, just to reach the edge of the observable universe. Which should give you an impression of just how ridiculously, preposterously vast the distance we are talking about is. It certainly made me laugh when I was trying to work it out with Google’s calculator.

The outer reaches of the Universe lay beyond comprehension. But that feeling of absurdity we’ve stirred must be similar to what people were thinking back when scientists busied themselves with a (comparatively modest) goal. Break free from the planet, reach the coast of outer space.

Like any era or event we try to categorize, the Space Race is really difficult to pin down with exact precision. However, it’s fair to say that the scheming and brainwork began in the 1940s. This was when we had a real chance of getting there, and the story of space exploration began.

For most of the early years, many nations, and in particular Russia and the US, struggled to get something to orbit. It wasn’t until 1957 that Russia would be the first to succeed with the launch of Sputnik 1, which stayed in orbit for three months.

Russia would even put the first man in space: cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin in 1961. Yet it is the Moon landing that, perhaps due to its role in the media of popular culture, made the deepest impression in the western collective unconscious.

When Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and crew landed on the Moon in 1969, the footage of the achievement captured hearts and minds across the globe. My Dad once told me it had been broadcast in his school in Morley, a market town on the outskirts of Leeds. He recalled all the pupils at the school huddled around a tiny T.V watching the grainy black and white footage. Such was the importance of the event, everyone had to see it.

The moon landing changed many attitudes towards Space. No longer was it this impossible, unsolvable conundrum. No. Now it was something we had a grip on. It may have appeared that all of Space was ours for the taking.

Now the sad part of the tale is that the early enthusiasm turned out to be overly optimistic: though we see progress in the news and online, for example the Mars rovers, the sense that we will soon go to the far corners of the universe has more than dwindled. Many, including Bill Bryson in the opening chapters of A Brief History of Everything, say it has receded to impossibility. Space is simply too vast.

Supposedly, it’s the things we can’t have we want most. I contend that it’s the slither of possibility, that decimal chance that we might, just might, have a shot that gets our heart thumping and our imagination whirring. Space was more exciting for more people when mastering it seemed almost imminent. It’s not when we can’t have something that we are interested. But when you have a telescope, television, or anything to show you that which is just slightly out of reach.

While the wave of excitement for spaceflight may have broken, the sea is not still. There is an increasing amount of commercial interest; Virgin Galactic is one such endeavour, and organisations set up by governments have for years been continuing their efforts, even if they haven’t been able to generate the same fever over a spectacle, and public involvement is something they continue to maintain at NASA.

NASA, an acronym for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, was established back in 1958 by US president Eisenhower, who would later be remembered for his remarks on the military-industrial complex. NASA is the agency behind the Apollo missions, Mars Rover, and undoubtedly the symbol of spaceflight for the majority of westerners.

And you can see an astronaut from their team, this November, at TEDxSalford 3.0.

A man who realised his dream after having many applications to NASA rejected. But he didn’t give up. His will and determination are exemplary. His relentless sense of trajectory and perseverance toward goals, the traits you would expect from a NASA recruit, paid off.

Getting work at a place like NASA may seem as inaccessible as the Moon does to a boy without a telescope. But our speaker eventually got that role at NASA; has spent roughly 167 days in Space, with considerable amount of time onboard the International Space Station; and has been a crew member on that most iconic space shuttle – Discovery.

We’re thrilled to announce that On November 10th 2013 we will be joined by a NASA astronaut who can share his experience with us, and shine light into the darkness of space. Because bringing a human face to something as inaccessible as space brings home to us the out of reach.

Be part of TEDxSalford 3.0 at the Lowry Complex, Salford Quays, Greater Manchester, on 10th November 2013. Tickets are now available. To know more, check out our speaker page where you can be introduced to the fascinating people speaking at the conference.

Related Posts

Martin Lindley

Martin is a Manchester based writer; he was one winner of National Flash Fiction day 2012, a finalist in BBC playwriting competition Write by the Quays, and short-listed for Student Journalist of the Year while he was at Uni. His fictions have been published by Blank Media, Bad Language, and TwentyTwo. He works in a bookshop.

Exploring Mars: The First Pictures from Curiosity’s Landing

Exploring Mars: The First Pictures from Curiosity’s Landing

Up In The Air, With The Jetman

Up In The Air, With The Jetman

The Inaccuracies of Eyewitness Testimony – Part 3

The Inaccuracies of Eyewitness Testimony – Part 3